Getting Lost in the Gaze

Hamutal Shapira

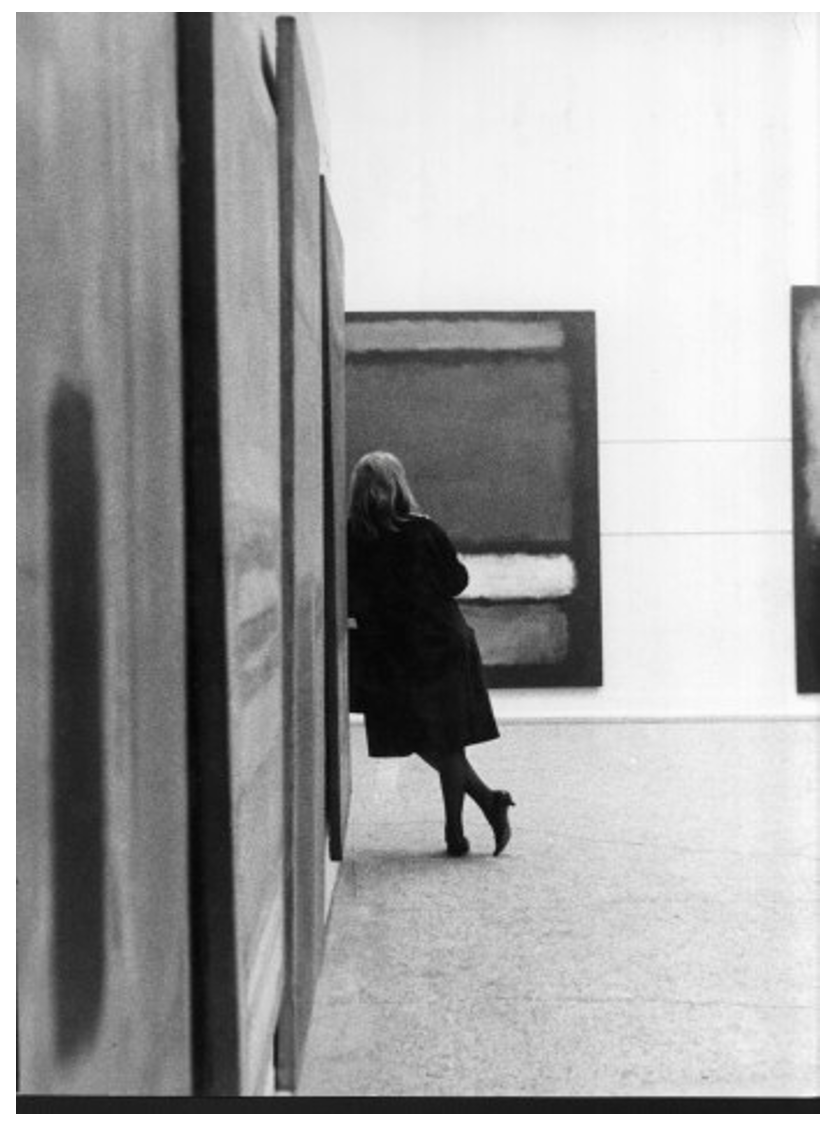

“A painting is not a picture of an experience; it is an experience.” (1) A current exhibition in Paris featuring the works of Mark Rothko (2) highlights this.

“What catches in its trap the observer, that is to say, us…what is the desire which is caught, fixed in the picture, but which also urges the artist to put something into operation? And what is that something? (3) […] what occurs as these strokes, which go to make up the miracle of the picture, fall like rain from the painter’s brush is not choice, but something else. Can we try to formulate what this something else is?” (4)

When looking at Mark Rothko’s big canvases, mostly those from his later period (from 1960 until his tragic death in 1970), it seems that “this something else” has to do with feminine jouissance.

During this period, with some exceptions, the darkened palette dominated Rothko’s work. He developed a painstaking technique of overlaying colors until, in the words of art historian Dore Ashton, “his surfaces were velvety as poems of the night.” (5)

“We no longer look at a painting as we did in the 19th century,” he says, “we are meant to enter it, to sink into its atmosphere of mist and light or to draw it around us like a coat, or a skin... we get enveloped within it.” (6) The signifier “enveloped” echoes Lacan’s formulation on the feminine: “Feminine sexuality appears as the effort of a jouissance enveloped in its own contiguity,” (7) the jouissance of a woman, of her own body, and not that of the body of the Other. Jouissance enveloped in its own contiguity, which points to a structure that has no outside, which conveys the infinite, to an uncountable continuum. It is jouissance as in a “whirling geyser of inexhaustible life, that cannot be said, that is not susceptible to castration: a jouissance reduced to the body event.” (8)

With Rothko you lay your gaze as “one lays down one’s weapons,” in the words of Lacan, on a non-image, blurred contour, endless fields of color, which lead to an ambiguous space. A space where shapes cannot be firmly bound, easily located, or securely identified. An area that is not caught up in the dialectic of flatness and depth.

Contemplating these limitless, infinite fields of color where there is no space between various overlaid brush strokes, touches the body, makes you feel engulfed, totally surrounded and can make one feel lost.

Rothko calls this the “spirit of myth”; “I became a painter because I wanted to raise painting to the level of poignancy of music and poetry […] my picture deals not with the particular anecdote, but rather with the spirit myth.” (9)

I suggest that, with Lacan, this can be called the spirit of the bar (Ⱥ), from which the Other is absent, “joui-absence”, which is essential to the feminine. “The jouissance of disappearance in its different forms, jouissance of the bar itself.” (10)

Then is it possible to say that to get lost in the gaze can be a name of feminine jouissance when contemplating a Rothko?

References

(1) Seiberling, D., “Mark Rothko” in LIFE Magazine, November 16, 1959, p. 82.

(2) https://www.fondationlouisvuitton.fr/en/events/mark-rothko , until 2 April 2024.

(3) Lacan, J., The Seminar of Jacques Lacan Book XI, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, ed. J.-A. Miller, trans. A. Sheridan, New York/London: Norton, 1977, p. 92.

(4) Ibid., p.114

(5) Cf. Dore, A., “About Rothko,” Boston: DeCapo Press, 1983.

(6) Breslin, J. E., The sorrow and the pity: Mark Rothko revisited, University of Chicago Press, 1993.

(7) Lacan, J., “Guiding Remarks for a Congress on Feminine Sexuality,” Écrits, trans. B. Fink, New York/London: Norton, 2006, p. 735.

(8) Miller, J.-A., “L’orientation lacanienne. L’Un-tout-Seul,” teaching delivered under the auspices of the Department of Psychoanalysis, University of Paris 8, lesson of 2 March 2011.

(9) Breslin, J. E., “The sorrow and the Pity: Mark Rothko Revisited,” Univ. of Chicago Press, 1993.

(10) References Brousse, M.-H., “The Feminine, A Mode of Jouissance,” WAP Libretto Series, New York: Lacanian Press, 2022, p. 63.